By Ashley Mehra

Professor Andromachi Tseloni is the Academic Lead for the Ministry of Justice’s Data First programme. Data First is an ADR UK-funded initiative to link data from across the family, civil, and criminal courts to better understand use of the justice system. The following is an interview with Professor Tseloni on her work and the Data First programme by our Editor, Ashley.

Your own research, including the Violence Trends Project, uses the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) to conduct analyses. Could you share with us the usefulness of victimisation surveys like the CSEW in your own work?

Thank you very much for contacting me and the great opportunity to reach out to members of the Centre for the Study of Global Human Movement.

Crime victimisation surveys (referred to as crime surveys henceforth) have played and continue to play central role in the development of the field of criminology and related scientific areas, such as policing, socio-legal studies, social psychology, and public health (to name just a few) since the late 1970s and in my own career since 1990.

Crime surveys of a national scale, like the CSEW, offer unique insights about the level, nature, risk/protective factors, consequences and public perceptions of crime and the criminal justice system. They collect data from randomly selected nationally representative population samples, including both non-victims and victims of crime. For this reason, they offer the most reliable estimates of national (and depending on adequate sample sizes regional) crime rates (at least for volume crime types, such as violence, theft, burglary, and car crime). These crime rates do not refer just to the number of offences (which are available in police data) but also to the number of victims in the population. These two (estimated) counts hardly ever coincide. Therefore, thanks to studies relying on crime survey data, the phenomena of multiple, repeat and series victimisation and additional crime rates on crime concentration, repeat crimes and repeat victimisation have been developed and are routinely used in academic discourse and crime prevention practice.

Furthermore, crime surveys use the same questions to elicit counts for each crime type since their advent – the CSEW since 1982. These questions are not influenced by changes in offence classification /legal definitions over time or recording practices across police forces. Emerging crime types, such as cyber – enabled crimes, enter the survey data in such a way that does not affect crime trends. For this reason, crime surveys offer robust estimates of crime, including violence trends and crime rates’ comparisons across jurisdictions. International crime surveys use the same questionnaire and methodology to provide robust cross-national crime comparisons and trends. Therefore, measurements of crime and associated harms are only possible with consistent crime survey data which shed light on the true scale of the problem and its implications for victims and the general population.

For example, one current policy interest (that feeds into policing) revolves around crime harm - how it can be measured to reflect crime seriousness and therefore inform policing priorities. The CSEW contains invaluable information for addressing crime harm justly in an equitable victim -centred manner.

In addition to crime and harm measurement, the lifestyle/routine activities victimisation theory and its numerous empirical tests, repeat victimisation theory, victimisation inequalities, crime perceptions studies, the security hypothesis for the crime drop, equity of the crime drop, and several other theoretical developments (e.g. fear of crime; trust to the criminal justice system; and collective efficacy) were all founded on crime survey data.

Beyond criminological theory and testing, evidence grounded on consistent findings from analyses of crime survey data have fed into successful crime prevention initiatives and evidence-based proactive rather than reactive policing. See, for example, the great impact of proactively policing repeat victimisation that warrants renewed interest.

More recently, a Nottingham Crime and Drugs Partnership initiative that relied on CSEW data helped to successfully reduce burglaries by 64% a year after its implementation. The above CSEW – based evidence on target hardening is now one of the initiatives police forces are advised to consider in order to access the Home Office Safer Streets Fund to tackle acquisitive crime.

After winning the ONS Research Excellence Award 2019, this research was described by the ONS’ Interim Deputy National Statistician, ‘The results of her project are already being used to make people and their property safer, highlighting the power of data in making better decisions and improving the lives of people in the UK’. The most recent ONS Research Excellence Awards 2020 commended another CSEW-based study, this year on alcohol-related violence, for collaboration and impact.

If (a) crime survey data did not exist or (b) non-government researchers were unable to access and analyse it, I would have had to work in another area of research!

Your own academic work has led to practical changes in policy. For instance, your work on burglary security is now used by the Neighborhood Watch Network, Office for National Statistics, and Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire Police. What advice would you give to academics on how they can effectively translate their research findings to the policy arena?

Social scientists are lucky to delve into knowledge gaps and produce insights which readily tap into policy issues. Whether this knowledge is actually ever used to inform policy is a combination of opportunity and politics. Therefore, in my view, researchers should not beat themselves up if their findings remain unexplored in the policy arena.

Having said this, academics can take some simple steps to translate their research findings into recommendations addressing policy evidence gaps and thus increase the chances of their practical use. From my own experience, there are four very effective steps:

First, map and get in touch with potential research users, such as charities, private and public sector organisations, and data owners;

Second, collaborate with key research users right from the start when formulating the research questions to be explored but - to avoid compromising scientific rigor and research independence – keep their contribution strictly consultative;

Third, regularly update potential research users and data owners with interim findings, inviting them to act (in an advisory capacity) as critical friends, to challenge the findings and to consider whether /how these findings are relevant for their day-to-day work;

Last but not least, keep an eye on the policy landscape. For example, calls for government consultations on matters apt to your expertise. Be also mindful of the partially different priorities and time scales between academic and policy/practice needs. Relatedly, be prepared to accommodate urgent calls to fill policy evidence gaps if the quick turnaround does not compromise the ethics and scientific rigor of such studies.

The ESRC offers detailed guidelines and ample support for researchers to develop their research impact; I was tremendously lucky to benefit from ESRC impact training very early on (in 2007). Since then I have participated in several ESRC - SDAI workshops on impact and now, as Data First Academic Lead, I used this very positive and empowering experience to suggest policy impact avenues for the ADR UK (Administrative Data Research UK) - funded Data First Research Fellows.

Can you give us a brief overview of the Data First project and its long-term goals?

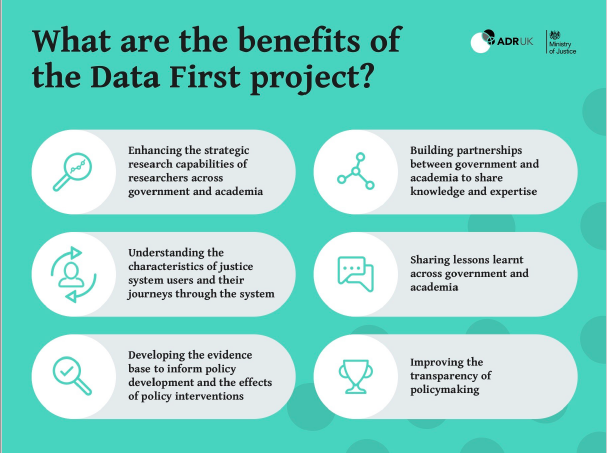

The Data First project is a data-linking programme led by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and funded by ADR UK, who in turn are funded by the ESRC. Data First aims to unlock the potential of the wealth of administrative data already created by MoJ and its executive agencies, such as Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) and HM Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS), in their day-to-day activities by converting them into anonymised, research-ready datasets. These datasets enable accredited researchers to access and analyse them in an ethical and responsible way.

Data First includes four workstreams:

- Data mapping and strategy digging into the abundance of administrative data with a view to develop an externally-shareable list of research-ready datasets – see, for example, the criminal courts linked dataset data catalogue;

- Internal data linking led by data scientists and data engineers to develop a robust, automated linking pipeline between criminal, family and civil justice datasets;

- External data linking of justice data with other government departments, such as the recently announced linked justice and education data; and

- Research, academic engagement and communications whereby social researchers and statisticians facilitate the link between Data First and the research and academic community and identify priority research questions to make best use of the linked datasets.

By working in partnership with academics to facilitate research in the justice space, Data First aims to create a sustainable body of knowledge on justice system users and their needs, pathways and outcomes across public services. This will provide evidence to underpin the development of government policies and drive real progress in tackling social and justice problems.

In order to further our understanding of this cohort, MoJ would also like to improve its data flows and internal and external data linking, strengthen strategic research capabilities, and enable more and better external research by providing academics with a sustainable and safe way in which they can access relevant anonymised data extracts. Therefore, Data First– based research will also create a feedback loop to the MoJ and other government departments about any administrative data limitations and gaps that thwart addressing important academic and policy evidence gaps.

Why do you think it is important to democratize and digitize access to datasets from across the justice system?

This work will allow us to fill many evidence gaps, improving the evidence base for public policy decision making and delivery. For example, we will increase our knowledge base for reducing re-offending. As broader data shares are created, we will increase the evidence base about the cohort of users of cross government services with multiple complex needs.

Data First will provide an evidence base for: public policy decision-making; for public service delivery for decisions which are likely to significantly benefit the UK, economy, society or quality of life of people in the UK; for improving Official Statistics; significantly extending understanding of social or economic trends or events by improving knowledge; and improving the quality, coverage or presentation of existing statistical information. Therefore, it holds the potential to benefit the following stakeholders:

- The public;

- Justice system’s users and their families, communities and social networks;

- Charitable organisations working with justice users;

- The courts and the criminal justice system (police, judiciary, probation and prison) and those working in these domains;

- Other Government Departments involved in justice data sharing;

- The economy; and the UK society (current and future generations) contributing to flourishing communities and meaningful lives for each individual.

What avenues of research will the linked administrative datasets offer to researchers?

Data First, one of the first strategically important programmes for ADR UK driven by a UK government department, will offer unique insights about the users of the criminal, civil and family justice systems: who they are; how frequently they use our services; and how they interact with broader public services across Government, with the aim of improving (and/or reducing) their interactions with the justice system and other public services.

Our research priorities include cross-cutting issues of equality and diversity; health and wellbeing; intersectionality; space and place; pathways and outcomes; relationships and trust; as well as perceptions of the justice system. In alignment with these priorities, some pertinent policy questions for interested researchers may include:

- How do protected characteristics and socio-demographic differences impact upon interactions with the justice system? (Equality and diversity)

- How can we ensure the right level of support for those with health conditions, particularly mental health and neurodevelopmental disorders, at all stages in the justice system? (Health and wellbeing)

- How do we ensure that prisons are decent, safe and productive places to live and work? (Space and place)

- How do we reduce rates of reoffending and improve life chances? (Pathways and outcomes)

For a comprehensive list of research questions, see this MoJ report.

Our readers are primarily interested in immigration-related research.

At the most recent Crime Surveys Users Conference, you and Eleftherios Nomikos showed that immigration in the UK has risen, in opposition to the sharp crime drop observed in the 1990s. How do you think this asymmetry revises our understanding of the association between immigration and criminality?

Lef’s PhD examines the role of immigration to the crime drop in England and Wales based on CSEW data. In his view, this asymmetry confirms the positive effects of immigration in England and Wales which have also been found in other English-speaking countries. It also shows that immigrants and also ethnic minorities (the two groups overlap as around 65% are immigrants) have a lower risk of assault victimisation. The above evidence raises questions as to why, and while we have an array of viable theoretical suggestions, these need to be further examined. We need to analyse contextual information on residential stability and assess whether social cohesion may be stronger within historically immigrants’ areas residence.

Readers might be interested in related work by Dr Dainis Ignatans - University of Huddersfield and University of Daugavpils (Latvia) - on the crime drop; area crime concentration; and perceived offence seriousness.

We glean from the CSEW data that it includes criteria on respondents’ self-reported ethnic background, whether they were born in the UK, fear of crime, etc. Could you expand upon what other kinds of information researchers can gain from the crime survey data with regards to immigration?

As you said, the CSEW includes amongst other demographic and socio-economic data, information on whether the respondent was born in the UK and self-reported ethnicity of both the respondent and her/his Household Representative Person. This can be analysed in conjunction with: (a) factual information, for example, on victimisation by specific crime types and any contact with the police and/or other justice agencies during the 12 months preceding the CSEW interview; (b) respondents’ perceptions / attitudes about crime, anti-social behaviour, and the criminal justice system and self-reported activities, such as alcohol and drug use, or past (before the 12-month reference period) experiences, such as historic abuse; and (c) interviewers’ assessment of the dwelling and area – all of which is collected in the CSEW.

Furthermore, estimates of rates of hate crimes by crime type are based on victims’ perception about the offenders’ motives via the following CSEW question:

“… do you think the person who did this picked on you because of any of these things?

1. Your skin colour or racial background

2. Your religious background (for example Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu)

3. A long term illness or disability you have

4. None of these”

Another question that may be of interest to readers is the following on respondents’ trust of the police:

“The police treat everyone fairly whatever their skin colour or religion.”

These are just some examples; the CSEW can be used to inform studies on immigration and crime, including perceptions via investigations based on any of the above information.

The rich (and to a large extent over time consistent) CSEW data and administrative justice data linkages provided by the MoJ ADR UK Data First project also open up multiple avenues for testing ‘crimmigration’ and suggesting alternative evidence-based theories that inform policy, such as Lef’s PhD study.

Thank you for your time and thoughtful responses, Professor Tseloni.

If readers have additional questions about the Data First programme, or more broadly about quantitative criminology, you may reach out to andromachi.tseloni@justice.gov.uk.