By: Dr. Petra Molnar

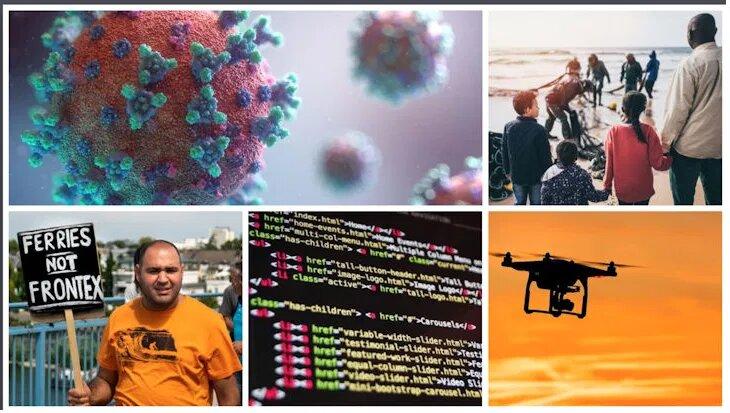

As the ‘Feared Outsiders’, refugees, immigrants, and people on the move have long been linked with bringing disease and illness across borders. During periods of immigration in 20th century America, for instance, immigrants were continuously stigmatized as carriers of germs and contagion. In the media and politics today, people crossing borders, whether by force or by choice, are described in apocalyptic terms like ‘flood’ or ‘wave,’ underscored by growing xenophobia and racism. Elected leaders like Poland’s Kaczynski and Hungary’s Orban capitalize on incendiary rhetoric of immigrants carrying ‘parasites and protozoa’ and blame various diseases on refugees. Of course, no list would be complete without the US President Trump’s increasingly violent rhetoric against migrants, including their apparent ‘tremendous medical problems’ that necessitate building a costly border wall. Not only are these links blatantly incorrect, but they also legitimize far-reaching state incursions and increasingly hard-line policies of surveillance and novel technical ‘solutions’ to manage migration.

These practices have become all the more apparent in the current global fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

As more states move toward a model of bio-surveillance to contain the spread of the pandemic, we are seeing an increase of tracking, automated drones to monitor lockdown compliance, and other types of technologies developed by the private sector purporting to help manage migration and stop the spread of the virus. In a matter of a few weeks, we have seen Big Tech present a variety of ‘solutions’ to governments for fighting the coronavirus sweeping the globe. Coupled with extraordinary state powers, the incursion of the private sector leaves open the possibility of grave human rights abuses and far reaching effects on civil liberties, particularly for communities on the margins. Emergency powers can be legitimate if grounded in both science and the need to protect health and safety, but we must be cognizant of history which shows that states can commit abuses in times of exception. New technologies can often facilitate these abuses, particularly against already marginalized communities. [i]

If previous use of technology is any indication, refugees and people on the move will be disproportionately targeted. Once tools like so-called virus-killing robots, cell phone tracking, and ‘artificially intelligent thermal cameras’ are turned against people crossing borders, the ramifications will be far reaching. Making people on the move more trackable and detectable justifies the use of more technology and data collection in the name of public health and national security.

Since before the current pandemic, my team and I have been documenting a worldwide roll-out of migration ‘techno-solutionism.’ These technological experiments occur at many points throughout a person’s journey. Well before you even cross a border, Big Data analytics are used to predict your movement and biometric data is collected about you. At European borders, AI lie detectors and facial recognition have started to be deployed to scan people’s faces for signs of deception. Beyond the border, algorithms have made their way into complex decision-making in immigration and refugee determinations, normally undertaken by human officers. Our past research with the International Human Rights Program and The CitizenLab at the University of Toronto has shown that migration technological experiments often discriminate, breach privacy, and even endanger lives.[ii]

In some cases, increased technology at the border has sadly already meant increased deaths. In late 2019, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, commonly known as Frontex, announced a new border strategy which relies on increased staff and new technology. This strategy includes its ROBORDER project which ‘aims to create a fully functional autonomous border surveillance system with unmanned mobile robots including aerial, water surface, underwater and ground vehicles.’ In the U.S., similar ‘smart-border’ technologies have been called a more ‘humane’ alternative to the Trump Administration’s calls for a physical wall. However, these technologies can have drastic results. For example, border control policies that use new surveillance technologies along the US–Mexico border have actually doubled migrant deaths and pushed migration routes towards more dangerous terrain through the Arizona desert, creating what anthropologist Jason De Leon calls a ‘land of open graves’. Given that the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has reported that, due to recent shipwrecks, over 20,000 people have already died trying to cross the Mediterranean since 2014, we can only imagine how many more bodies will wash upon the shores of Europe as the situation worsens in Greece and Turkey.

The COVID pandemic will not only affect people trying to cross borders, but will also severely impact refugees living in informal settlements or securitized camps. Cases have already been reported on the Greek Island of Lesbos, which has been hosting hundreds of thousands of refugees since the start of the Syrian war in 2011. Italy has also announced that it has closed its ports to refugee ships until July 31 because of coronavirus. However, the answer to stopping the spread of the virus is not increased surveillance through new technology, building new detention camps, and preventing access into the camps for NGO workers and medical personnel. Instead, we need a redistribution of vital resources, free access to healthcare for all regardless of immigration status, and more empathy and kindness towards people crossing borders.

Pandemic responses are very clearly political. While human movement may have stalled, people will continue to cross borders, whether out of necessity, by choice or a little bit of both. It is incumbent upon us to pay close attention to how the rhetoric around migration and disease is weaponized by those in power and what types of linkages we take as necessities in our global fight against a life-threatening pandemic. These tropes are deeply ingrained: even before the current outbreak of COVID-19, the Trump administration sought to use the spectre of disease linked to immigrants to increase its draconian policies to close borders – they tried with mumps and the flu, but perhaps they will succeed with COVID-19.

The development and deployment of technology is also a political exercise.[iii] While shiny new tech tools can offer the promise of novel solutions for an unprecedented global crisis, we must ensure that COVID-19 technology does not unfairly target refugees, racialized communities, the Indigenous communities, and other marginalized groups, and make discriminatory inferences that can lead to detention, family separation, and other irreparable harms. Technological tools can quickly become tools of oppression and surveillance, denying people agency and dignity and contributing to a global climate that is increasingly more hostile to people on the move. It is very troubling when private companies like Palantir Technologies, linked to a host of human rights abuses including the targeting of people for detention and deportation in the United States, have now become the preferred vendor for various governments, even working with the NHS on their response to the pandemic. Surviving and coming up with viable solutions to this complex global health crisis lies beyond the hubris of Big Tech thinking it has all the answers – “answers” which often exacerbate profound inequities and power differentials in our world.

Most importantly, technological solutions do not address the root causes of displacement, forced migration, and economic inequality, all of which exacerbate the spread of global pandemics like COVID-19. In order to address the complex global health crisis we face today, it is imperative that we remember: unless all of us are healthy, no one is.

[i] Molnar, P. (2019). Technologies on the Margins: AI and global migration management from a human rights perspective, Cambridge International Law Journal 8(2).

[ii] Molnar, P. and Gill, L. (2018) Bots at the Gate: A Human Rights Analysis of Automated Decision-Making in Canada’s Refugee and Immigration System University of Toronto. Online: https://ihrp.law.utoronto.ca/sites/default/files/media/IHRP-Automated-Systems-Report-Web.pdf

[iii] Molnar P. and Naranjo, D. (2020). Surveillance Won’t Stop the Coronavirus. New York Times. 15 April 2020. Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/15/opinion/coronavirus-surveillance-privacy-rights.html

Petra Molnar is the Director of the International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Law and a Mozilla Fellow working with EDRi on AI and migration. She has worked on forced migration and refugee issues since 2008 as a settlement worker, researcher, and lawyer. Petra earned her LL.M. in 2019 from the University of Cambridge, Darwin College.