By: Ashley Mehra, Dr John G. Dale

This article is part of our ongoing series on Technology and Human Rights.

Blockchain technology in global supply chains has proven most useful as a tool for storing and keeping records of information or facilitating payments with increased efficiency. The use of blockchain to improve supply chains for humanitarian projects has mushroomed over the last five years; this increased popularity is in large part due to the potential for transparency and security that the design of the technology proposes to offer. Yet, we want to ask an important but largely unexplored question in the academic literature about the human rights of the workers who produce these “humanitarian blockchain” solutions: “How can blockchain help eliminate extensive labor exploitation issues embedded within our global supply chains?”

To begin to answer this question, we suggest that proposed humanitarian blockchain solutions must (1) re-purpose the technical affordances of blockchain to address relations of power that, sometimes unwittingly, exploit and prevent workers from collectively exercising their voice; (2) include legally or socially enforceable mechanisms that enable workers to meaningfully voice their knowledge of working conditions without fear of retaliation; and (3) re-frame our current understanding of human rights issues in the context of supply chains to include the labor exploitation within supply chains that produce and sustain the blockchain itself.

Covid-19 Has Exposed Our Interdependence

The coronavirus pandemic has brought to the forefront just how much we depend on exploited labor for supplying us with our everyday essentials, from the foods we eat to the toiletries we buy online to the clothes we wear on our backs. From this past week’s headlines alone, we learned that workers at Smithfield Foods – most of whom are immigrants and refugees – alleged that the company ignored their persistent requests for personal protective equipment and pressured them to return to work, leading to an outbreak at one of the processing plants that became the worst coronavirus cluster in the US; now, a group of workers are suing the company for poor working conditions. Hundreds of tech and warehouse workers at Amazon united to stage a “sick-out,” refusing to show up for work in order to pressure the company to enact necessary safety measures to protect workers’ health. Garment workers in Bangladesh have taken to the streets, defying the country-wide lockdown, to demand they be paid the wages they earned the past two months before the coronavirus caused many factories to shut down.

We are learning hard lessons about just how transnationally connected and interdependent we are as a society – both socially and economically. While “social (or more accurately, physical) distancing” may help us “flatten the curve” of the number of people among us contracting the virus, we cannot easily wash our hands of the disruption Covid-19 has wrought on the supply chains that we, until now, have taken for granted.

Blockchain Repurposed for Humanitarian and Human Rights Problems

Technologists have proposed blockchain (see Inset 1) as a potential solution to many of our supply chain problems — including labor exploitation and other abusive human rights interactions and practices that flow through them.

Originally created in 2008 by the open-source Bitcoin community to allow reliable peer-to-peer financial transactions, blockchain technology is a type of distributed ledger technology (DLT) that records transactions in encryptable digital code without the need for government-backed intermediaries or any third-party platforms. Technologists applaud the potential for the decentralized and “trustless” infrastructure underlying blockchain to reduce corruption by enhancing transparency and accountability across peer-to-peer networks. Beyond the impact envisioned for the financial sector, actors across all sectors — business, government, civil society, and social enterprise — are exploring new applications for blockchain technology (blockchain 2.0) in the fields of digital identity, smart contracts, and supply chain management.

In their article, “Blockchain for Good?,” Kewell, Adams, and Parry explain that the intended use built into the design of an artefact, such as a DLT, is distinct from the properties which it assumes. Thus, the same artefact can be used in different (though not unlimited) ways – toward different ends and re-designed to accord with different ethical principles. Now, many humanitarian and development organizations, as well as social enterprises (legally structured to prioritize their social problem-solving missions over their profits) are combining funding instruments with blockchain technology in the hope of increasing efficiency, transparency, and accountability. Blockchain for social impact has inspired a huge array of projects that repurpose blockchain technology to store information of all kinds – the Blockchain Trust Accelerator at New America and Blockchange at GovLab are each collecting hundreds of blockchain impact projects into a register. “Humanitarian blockchain” is a term commonly used to refer to efforts that design blockchain for application in projects that address humanitarian crises and human rights abuses.

_____

Inset 1. Blockchain and Its Basic Consensus Mechanism

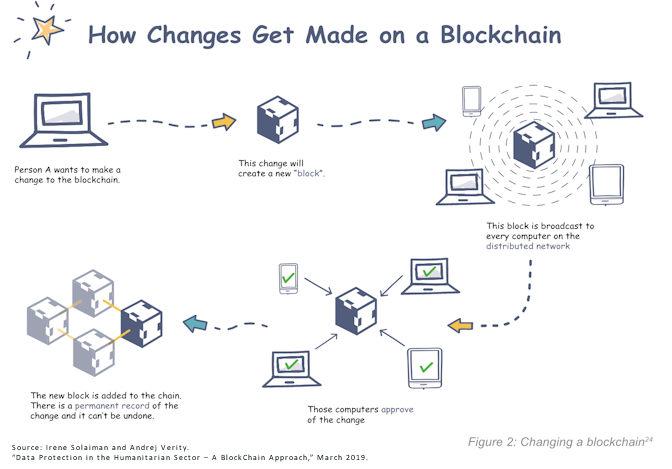

Here is a brief primer on how blockchain, and its basic consensus mechanism, works: data is inputted into the blockchain as a “block”; the block’s content is time stamped and the block is given a unique identification code, or “hash”. Hashing is a way of verifying the authenticity of the transactions, allowing users to identify whether someone or something has intervened with the data. Neither the block, nor its contents, nor the order of the blocks in the chain may be adjusted once sealed; altering the contents of one block will render the following blocks invalid, thus breaking the chain. “Proof of work” slows the creation of new blocks, such that all new and adjusted blocks must be agreed upon by consensus.

Source: Irene Solaiman and Andrej Verity. “Data Protection in the Humanitarian Sector – A BlockChain Approach,” March 2019.

_____

Increasingly, blockchain technology is promoted by governments, corporations, and human rights advocates as a cutting-edge tool for addressing even the most intractable humanitarian and human rights issues, including those that acutely affect refugees like food insecurity. For example, the UN World Food Programme’s “Building Blocks” project (started in 2016) has used blockchain for aid distribution to refugees in Jordanian camps; the programme has been able to reduce costs of bank transfer fees by 98% and allow for greater anonymity by encrypting the personal information of refugees who collect assistance.

World Wildlife Fund’s “bait-to-plate” program best exemplifies a more common application of blockchain to labor exploitation issues in particular: the program uses a combination of radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags and quick response (QR) codes to attach to a food, like tuna fish, to a blockchain; consumers can follow on their smartphone the product’s journey along the supply chain by scanning the QR code of the product. A key limitation of such blockchain solutions to labor exploitation is the priority on tracing the commodity itself rather than addressing the labor conditions of commodity production.

The blockchain might in fact reinforce that a commodity is clean because the data along the supply chain reads as such. Yet, simply recording the journey of the commodity does not necessarily preclude bad actors from inputting fraudulent data; data can be corrupted at the first instance of input. Rather than attempting to change the social relationship between labor and capital, humanitarian blockchain in this way might enable the disappearance of human labor into capital, enabling a misconception of a global supply chain “clean” of exploited labor.

So, why are producers in industries like food and finance now turning to blockchain solutions to rid their supply chains of labor exploitation? Three key reasons are increasing regulatory pressure, concerns about social metrics, and the need to mitigate security risks. Furthermore, the contemporary governance of global supply chains is increasingly reliant on “social auditing” – an ethical and voluntary benchmarking regime supported by both corporations and civil society groups – to ensure that companies identify and demonstrate efforts toward remediating forced labor within their supply chains.

Blockchain Is a Social Technology, and Not Just a Digital Tool

Blockchain is designed to re-engineer social networks and the ways that power is distributed within them – with not only online, but also offline consequences. Simply integrating digital technology into the process does not provide workers with binding and enforceable mechanisms through which they can demand respect for their rights without fear of reprisal.

For example, “worker voice” tools (WVT) strive to give workers the ability to voice their grievances to employers. A pilot program proposed by the State Department, Harvard, Consensys, and other partners is building a worker well-being database with technology-enabled “worker wellbeing surveys” that are added in pseudo-anonymous form to a blockchain platform. Labor-management “participation committees” – often presented as a viable alternative to labor unions – bring together representatives of labor and employers to the table to discuss workers’ complaints.

As Kyritsis, LeBaron, and Anner (2019) observe,

The kind of “worker voice” tools that are designed to complement social auditing — instead of challenging the status quo — are structurally unable to fulfill their promise of empowering workers to improve their own labor conditions, because they do not provide workers with protected and collective [enforcement] mechanisms through which they can demand respect for their rights and improvements to their wages and conditions of work without fear of reprisal…[T]hus, allowing businesses to profit from labor exploitation with relative impunity.

To address the power structures underlying the relationship between exploited laborers and employers, as well as the very design of the technology meant to empower the voice of workers, requires greater attention to, and alignment between, the ethical principles shaping each. Two sets of principles, among others, have been independently proposed and are already addressing labor exploitation in supply chains – the Worker-Driven Social Responsibility (WSR) Principles and the Worker Engagement Supported by Technology (WEST Principles).

The WSR Principles grew from the Campaign for Fair Food led by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) – one of the first worker centers in the US dedicated to aiding migrants – to demand fairer standards and enforceable mechanisms that address human rights abuse in the tomato industry. The model suggests creating legally binding commitments that assign responsibility for improving working conditions to corporations at the top of supply chains and forming an independent body responsible for investigating complaints on behalf of workers’ interests. The emphasis of these principles is on the social organization of employers and workers and does not explicitly address digital technologies like worker voice tools per se. However, the WEST principles in combination with the WSR model might present an opportunity for developing enforceable mechanisms by means of technology-enabled solutions to attend to workers’ fears of employer retaliation when they voice their concerns, or opposition to exploitation.

To be clear, we are not presenting a “solution” or endorsing these particular principles as a coherent set of guidelines for ridding our supply chains of labor exploitation. Rather, we are providing an example of how principles like these, currently practiced in isolation, might be conjoined and built upon to improve the design of humanitarian blockchain technology in ways that defend and advance workers’ social agency to more meaningfully address labor exploitation in the supply chain. The need for such principles aligns with a recent initiative called “Clean Slate for Worker Power,” a project of the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School, which just launched a report in January 2020 that proposes bold, transformative recommendations for reorganizing power in the US system of labor laws to empower workers. The initiative includes the voice of technologists, suggesting that the reform of labor laws must “protect workers’ access to use the full panoply of employer technology” and allow workers to self-organize “digital meeting spaces…without employers’ surveillance of and interference with ad-hoc and informal online forums and spaces.”

If we can combine principles for the ethical design and application of blockchain with principles for organizing labor relations in ways that enable workers to enforce meaningful restrictions to their exploitation, then it seems possible to integrate into humanitarian blockchain the kinds of human rights standards that the United Nations has recently elaborated for adopting emerging technologies.

What’s in Your Platform? Or, Who Supplies the Blockchain to Supply Chains?

The labor that makes blockchain itself is not “unchained” from supply-chain labor exploitation. For blockchain to reach its full potential in addressing labor exploitation, we also must understand how this innovative technology is socially embedded in the labor conditions of the workers employed by tech start-ups and Big-Tech companies who design, source, produce, develop and maintain this technology, as well as the labs, campuses, infrastructure and platforms that enable it.

Abuses in the tech sector include wage theft; unpaid overtime; retaliation and intimidation tactics; sexual harassment; discrimination based on race, age, and religion; and poor, even dangerous, working conditions. In response, there has been a sharp rise over the past year in protests, walk outs, open letters, and other forms of collective action by tech workers, despite the considerable risk of employer retaliation. A project called Collective Actions in Tech is attempting to document these human rights abuses in the tech sector, as well as incidents of contentious collective action among workers in the global tech industry itself, through a publicly available online database. In this way, tech workers are building a different kind of “platform” to solve their own supply chain problem.

Thus, humanitarian blockchain cannot adequately solve the problem of labor exploitation in our supply chains without also addressing the labor exploitation in the supply chains that make humanitarian blockchain possible in the first place. Adopting blockchain as a solution to a given supply chain now renders blockchain’s own supply chain – and any labor exploitation existing within it – a part of the given supply chain. The problem is not merely a technical one, but also a political one, in the sense that it entails disrupting and re-organizing the relations of power at the heart of labor exploitation. That is, labor exploitation does not require only a technical solution, but also a democratic solution – one that can empower workers’ human dignity and agency and instantiate workers’ human rights and equality.

Ashley Mehra is a Visiting Scholar at the Centre and founding editor of the Global Human Movement Review. She earned an MPhil in Classics in 2019 as a Buckley Scholar at King’s College, Cambridge. Ashley is working with Professor Dale on a book manuscript as a graduate research assistant in the Science and Technology Innovation Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Dr. John G. Dale is an appointed Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. He serves on the Steering Committee of the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Science & Human Rights Coalition and as a Council Member of the American Sociological Association’s Section on Human Rights. His current research explores how big data and digital technologies reshape the practices and politics of human rights, and understandings of humanity.