Submitted by Edward Grierson on Tue, 30/07/2024 - 15:25

Refugee Week is about building, bridges but also combating indifference. Those of us who attended the Community Arts Festival for Cambridge Refugee Week on June 22, including myself, were likely supporters of refugees already. But few of us could be said to truly understand what they go through.

Having been born in the UK and lived here all my life, I have enjoyed the benefits of living in a stable, democratic country. I have never worried about being displaced or persecuted. And while I have been aware of those that are persecuted, I was not familiar with how it felt. I came to learn about it from refugees themselves.

Art and culture are some of the most effective ways of building bridges. Refugees can show the depth and complexity of their culture. In turn, natives can see that it is not something to fear. This was the format of the Community Arts Festival: bringing in refugees and others with affiliations to countries in conflict, to lead performances and workshops showcasing their home culture.

At the start of the day, I attended a geometry workshop by Iranian-born Cambridge artists Elmira and Ramona Zadissa. This workshop broke down many cultural stigmas. In the West, the abstract nature of Islamic art has sometimes been viewed negatively: an example of puritanical Islam, in contrast to the freedom offered by figurative art here. The Zadissas perfectly explained the concept behind this abstract process- “it honours the wonders of creation, using the skills God provided us, without trying to directly imitate him”. Having been raised in Sweden since childhood, the Zadissas also saw this as a way to maintain a connection with their culture.

It is also an art form based in mathematics, using geometry and repetition to create a myriad of patterns from geometric shapes. It shows that, while differing in approach, Eastern artistic traditions are just as complex as those in the West.

For some performers, their art was an expression of protest. Such was the case with the Afghan performers. These were Mirwaiss Sidiqi, musician and former country director of the Aga Khan Music Programme, and the father and son partnership Haroon and Homan Yousofi. Since the Taliban retook control of the country three years ago, music of all types has been outlawed. Zohra, the first Afghan women’s orchestra, have relocated. Meanwhile, staff from the music faculty of Kabul University were granted posts at Franz Liszt University in Weimar, Germany.

Sidiqi delved into the history and complexity of Afghan music. The country’s classical tradition uses a framework known as ragas, akin to classical Indian music. It involves a system of scales, and certain notes within each scale arranged in various ways.

These traditions go back at least as far as the Gandhara culture in the 2nd century BC. Since then, Kucheh Kharabat in Kabul has been a dedicated musician’s quarter, with a tradition of passing songs down orally. There are also distinct musical traditions among the Tajiks, Uzbeks, Baloch, and other minority groups. As Afghanistan has been part of empires centred in Iran and India, and been the centre of the Mughal Empire, there is a strong shared musical heritage across South Asia. Sidiqi summed it up by saying, “music is not an impassable mountain”. It is a fluid medium. Afghanistan’s musical traditions have crossed through its diverse cultures. And Afghan musicians taking refuge elsewhere can use it as a form of protest.

Homan, a poet and satirist, recited poetry about his sense of belonging and identity, accompanied by his father, Haroon, on the harmonium. Haroon was former teacher of Persian and Russian Literature at Kabul University, and Director of Television and Radio for Afghanistan’s government, before being forced to leave in 1990. His presence here was a reminder that even those with high standing in their home countries can become displaced. War and persecution are great levellers of status. In situations like that in Afghanistan, music is a powerful way of expressing resentment. But it can also bring that resentment to a wider audience. Homan Yousofi summarised this feeling as, “there is anger from the situation in Afghanistan, but it needs to be turned into positive action”. For many, that positive action can only happen if they have refuge in a free country.

Building bridges is particularly important to raise awareness of overlooked conflicts. Eritrea receives very little coverage in Western media. Yet an estimated 580,000 Eritreans applied for asylum globally in 2023. The country has been ruled as a one-party state since its independence from Ethiopia, enforcing mandatory conscription for indefinite lengths of time. Grmalem Kasa, a pottery artist, left Eritrea aged 14 to follow most of his family to Europe. Now he studies at the University of the Creative Arts (UCA). His work draws on Eritrean clay sculpting traditions, and at the festival he showed visitors how to make clay coffee pots.

Coffee is a major part of Eritrean culture, being part of the hospitality that homeowners are expected to provide guests. As such, it has become a way to bridge divides between Eritrea’s Christians and Muslims, and Eritreans and Ethiopians. Now, Kasa uses coffee pots to build bridges between Eritrean refugees and their host countries.

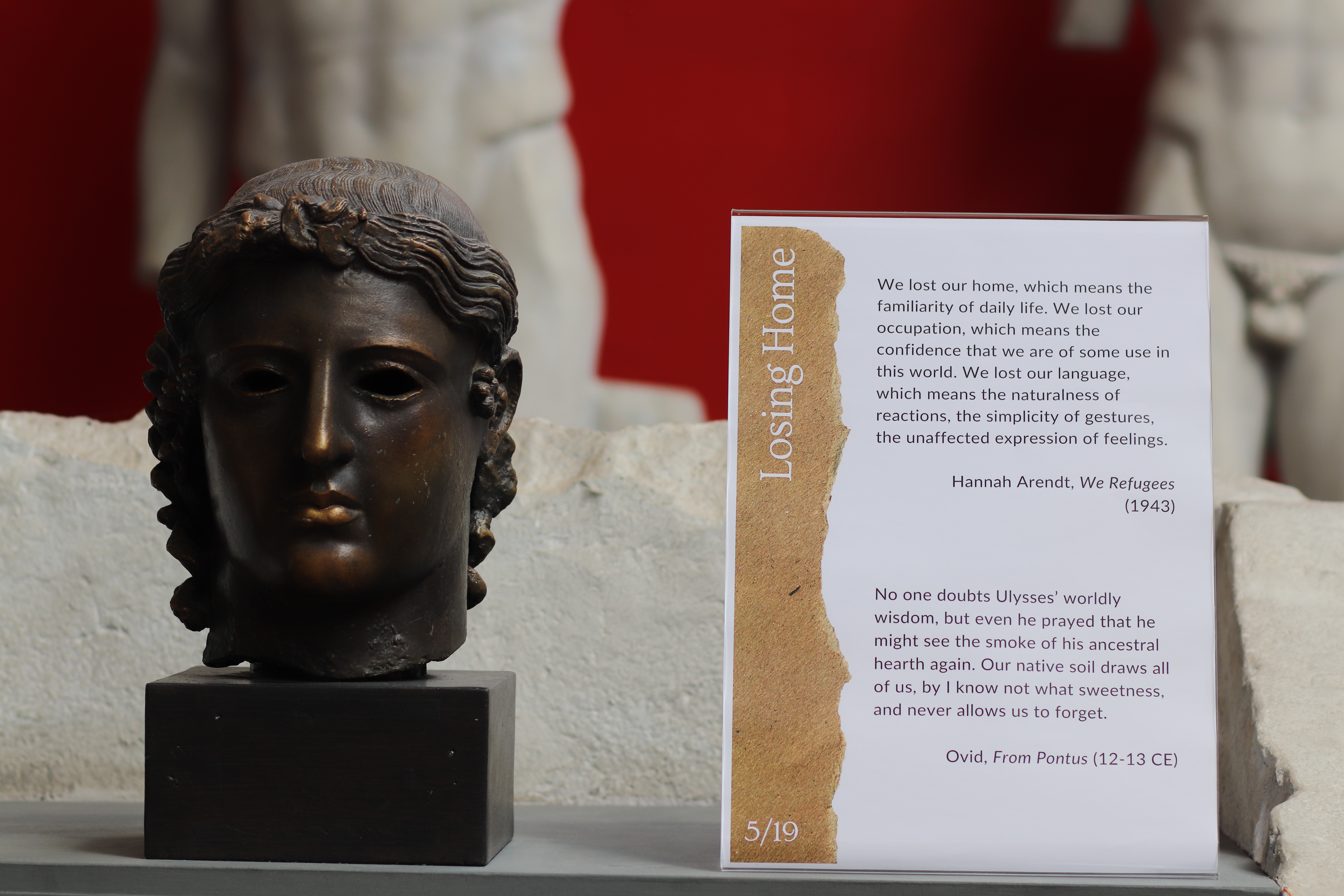

But if Refugee Week is about building bridges, those bridges also need to be built between the present and the past. As Europe becomes more insular, people are insisting on fortifying our borders to ‘defend European civilization’. But how did classical Greece and Rome, the supposed founders of this civilization, actually view refugees? The Museum of Classical Archaeology answered with a trail through their collection, based on the philosopher Hannah Arendt’s writing about refugees. There are many parallels with classical notions of refuge, and our modern understanding of refugees as defined by Arendt.

The Greek concept of ‘xenia’ meant granting hospitality to strangers. This was depicted in the Baucis and Philemon myth, with the characters being rewarded by Zeus and Hermes for sheltering them while disguised. Euripides depicted Medea being forced to leave Corinth, after a degree by Creon. He also portrayed the descendants of Heracles being attacked by Eurystheus and seeking refuge in Athens. Homer and Ovid wrote of Odysseus’ alienation and exhaustion from being adrift in the Mediterranean, unable to return home. The idea of refuge is ingrained in the Western canon.

One quote by Hannah Arendt stood out in the refugee trail: “refugees represent the vanguard of their people- if they keep their identity”. The cultural practices here, from poetry to pottery, were ways of for refugees to hold onto their identities in a foreign country.

But this process can also be transformative. Events such as the Community Arts Festival allow native citizens to learn about refugees’ experiences. They can show the diversity and beauty of other cultures. In doing so, they can displace the fears about refugees and immigrants’ relationship with their new country’s customs. I left this festival with more understanding of refugee struggles, from across history and the world.

Increasing understanding and with it, empathy, is how art and culture builds bridges.