Submitted by Dr T. Basaran on Sun, 27/12/2020 - 15:55

by Melissa Gatter

Melissa Gatter completed fieldwork in Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan during February and March 2016. Access to Za’atari was secured through an internship with the organization Save the Children whose offices are located in Amman. She supported the Media, Communications, and Advocacy department, researching and monitoring the ongoing conflict in Dar’a, Syria and making frequent visits to the camp to carry out case studies in the NGO’s centres and to make house visits. Melissa’s thesis will focus on the relationship between children and NGOs in Za’atari and its implications for changing notions of Syrianness.

Traveling down a reasonably busy two-lane road in Mafraq, we are passed by speeding cars, only to all but stop at the surprisingly high speed bumps (maTab) that seem to go against Jordan’s go-with-the-flow traffic culture. On the left are sprawling olive tree farms, dotting the otherwise desert scenery with green. On the right, a few modest carpenter shops and convenience stores are arranged in a row, with fresh produce for sale lining the road in front of them. A few children walk to school, and older men wearing the traditional red-and-white kaffiyeh headscarf also wander along the road to unknown destinations. We pass a few UNHCR tents set up in an empty area near the shops.

“Gypsies,” Hamza, the driver, and my coworker, tells me. A 26-year-old native of Irbid, Hamza lives and works in Amman as Save the Children’s Communications Coordinator. He loves driving in Amman—“it calms me”—and sings along to nineties American music while at the wheel, often also discussing the latest in American politics.

We arrive at a traffic stop. Young boys in sweatpants and t-shirts lounge about on the corner in rusty wheelbarrows waiting for work, some joking with a group of adults like little men. The road continues straight, but we turn right and pause under a sign that says, “Za’atari Refugee Camp, Mafraq Governorate, Jordan”. A large army car is seated just to the right of this checkpoint, and a soldier leans on the seat on top of the vehicle. Hamza hands an officer the car permit and shows him our badges. The officer returns the permit after a fleeting look into the car. “Ya’Tiikum al-‘afiyeh.” Refugee families coming in and out of this entrance show another officer their papers. They are on foot.

We continue on. Our car is modestly branded as Save the Children property; other cars on the road sport the blue UNHCR or UNICEF logos. The ‘no guns’ bumper sticker on our windshield means we are compliant with Jordanian laws regarding weapons in the refugee camp. “It also keeps us from being stopped as often for the random police inspections (taftiish) along the highway,” Hamza had mentioned.

We head down a long, narrow road wide enough for one lane of traffic, but NGO vehicles pass each other in opposite directions with ease. Hamza swerves in and out of people walking on the road, slowing down and giving a gentle beep of the horn as a warning. “When I first used to come here, I would turn off the music in the car when entering the camp and driving down this road, in solidarity with the refugees. But now I sing along and am happy because they are the first to sing and dance and clap.”

As we approach the official entrance to the camp, we pass boys pushing wheelbarrows full of sand and gravel, young men carrying heavy plastic bags, and women with children. We stop at the entrance, and Hamza hands a second officer the permit as a line of people awaits permission to enter at another security booth. The officer glances at me.

“SaHafiyyeh? (Is she a journalist?)” he asks Hamza. Hamza explains I am an employee of Save the Children. I hold up my red lanyard and badge. The officer nods and waves us on.

“It’s interesting he assumed you were a journalist,” Hamza notes as we drive into what is now the largest refugee camp in the world[i]. “They’re really very strict on letting journalists in now.”

Over the next month and a half, I joined Hamza on his routine of entering the base camp—a row of brightly marked caravans hosting the offices of the more than twenty NGOs operating in Za’atari—checking in with the staff there, and then driving to various Save the Children centres to complete our assignment for the day.

Za’atari is home to roughly 80,000 Syrian refugees in twelve districts. District 1 is the oldest and most densely populated area, where people fleeing from violence in Dar’a, Syria first settled four years ago. As time went on, more refugees filled in the other eleven districts, shifting to move near family members. The first refugees in Za’atari started what is today the Shams Élysées (الشام زيليزيه), a long market thoroughfare selling everything from cell phones to canaries to mini solar panels to Hariri chicken (named after a powerful family clan in the camp). Street names, like Shar’a al-Suq (Market Street, aka the Shams Élysées), Shar’a al-Warad (Flower Street), and Shar’a al-ItiHad (Union Street), are artfully painted on the side of caravans and provide a sense of direction. Houses are numbered and no two houses look the same, except for in the newer district, where new caravans have been donated by Saudi Arabia to provide for population growth and rearranging of some areas. Most have expanded their caravans with metal walls and old UNHCR tents that had been replaced by caravans. Many houses have modest patios or courtyards connected to a neighboring caravan. Others advertise a small convenience store, restaurant, or mosque run by the owners in their house, and many display messages such as “God is Great” (Allahu akbar) and “Pray to the Prophet” (Salii ‘ala al-nabi).

The road encircling the camp is called Ring Road (Shar’a al-Khaatim) and separates Za’atari from man-made ditches where Jordanian army vehicles are positioned at regular intervals. This road and the long road connecting the camp to Mafraq have been paved within the last year. The rest is gravel, laid on the desert sand when Za’atari was first set up in 2012 to prevent sandstorms and mud from rainfall, though both still occur. At the highest point of the camp sits a large square water tank, the roof of which provides a 360-degree view of the camp, as well as of Mafraq and the Za’atari village from which the camp gets its name. The white caravans, satellite dishes, and web of laundry lines against a sunset make for a breathtaking view, but not one to be celebrated. In the distance is Dar’a, Syria, where the uprising began—and from where over ninety percent of the refugees came.

Za’atari as we see it today is an outcome of both UN administrators and camp residents making concessions in the development of the camp. From observations made in 2013, Lionel Beehner describes the UN’s effort to create a geometrically sound space as being “driven by aesthetic impulses as much as they were by outcomes.”[ii] Indeed, looking at a current map of Za’atari, one notices neat rows of caravans and legible divisions.[iii] Creating a sense of order through organized urban planning would ensure that the UN and Jordanian government, who share joint leadership of Za’atari, maintain complete control. It was to be a ‘model’ refugee camp.

Courtesy of the UNHCR.

Over time, Syrian refugees in each district (generally belonging to each of the major large family clans in Dar’a or to the minority from the Damascus area) formed cul-de-sac-like neighborhoods with their closest relatives. The straight rows began to curve slightly, and the cookie-cutter caravans became personalized through art, gardening, and home expansion. The main market street, which begins near the base camp and passes by the medical clinic and one of the bread distribution centres, arose as an “unplanned ‘public space’”[iv] where many hang out even when not shopping. Other public areas such as schools and even the areas between homes arose as “spaces of vitality, busyness and social interaction.”

Much of this growth had camp administration struggling to keep up. This improvised shifting of living space and establishment of an informal economy was not in the UN’s blueprint, and the orderly assigned rows of the original plans were strange to Syrians. Former Senior Field Coordinator in the camp, Kilian Kleinschmidt, once said, with a nod toward Za’atari, “In the Middle East, we were building camps: storage facilities for people. But the refugees were building a city.”[v] The Syrians of Za’atari have become known for their resourcefulness—Beehner calls them “do-it-yourself refugees”.[vi]

Camp administration did the right thing by working to accommodate refugee innovation in finding a compromise between security interests and livability.[vii] Out of this, we witness the development of Za’atari into what Michel Agier calls a “city-camp”.[viii] Any visitor to Za’atari may note that it is quite developed—for a refugee camp. And while this development has restored some sense of normalcy for Syrians, it is at the same time an endless, “perpetually aborted” development. A Questscope aid worker told me, “People work and go to activities to feel like they’re on some sort of a forward-moving projectile.”[ix] But, she said, there is a ceiling to Za’atari’s development. Agier argues that it will never attain recognition as a city, but rather will always be seen as “a massive population of undesirables, kept in existence in spaces remote from everything.”[x]

This is because a refugee camp is intended to be a temporary solution. Jordan’s government, concerned with maintaining its seemingly impenetrable national security bubble and already struggling to provide for its own population, discourages refugee innovation or self-sustaining ways of living in the camps lest the Syrians replicate the actions of Palestinians before them. Marnie Thomson states, “Impermanence is designed into the refugees’ most intimate spaces. Their homes are constructed with destruction in mind.”[xi] Thus, urbanity and refugee activity in Za’atari becomes a mere reenactment of city life, a “necessary performance of will”.[xii]

All things considered, we must not underestimate this ‘performance’. While the concept of the refugee camp has been criticized as a device to merely keep refugees alive, Za’atari’s organizations offer many programs to empower and educate residents—like Katrine[xiii], a 16-year-old divorcee who advocates for girls to finish education before marriage; Miriam, a 19-year-old photojournalist-to-be who interviews others in the camp; and Abu Yaqub, a 50-year-old security guard who makes sure all thirteen of his children go to school.

Syrian resilience is real, and for many right now, the only hope. These are the communities who can rebuild their country upon return or bring ingenuity to new places upon resettlement. In the meantime, organizations should acknowledge the semi-permanence of the “forever temporary”[xiv] situation and continue their committed presence in residents’ lives. As long as Za’atari is dismissed as merely a refugee camp, all of its residents’ potential will be just that: potential.

The sun sets over Za’atari. Photo by the author.

Notes

[i] The largest camp, Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya, is allegedly being closed by the Kenyan government.

[ii] Lionel Beehner, “Are Syria’s Do-It-Yourself Refugees Outliers or Examples of a New Norm?,” Journal of International Affairs 68, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2015), pp. 165.

[iii]Za’atari is one of the first refugee camps to be mapped. This site offers several different types of maps: http://mc.bbbike.org/mc/?lon=36.33106&lat=32.29246&zoom=14&num=8&mt0=mapnik&mt1=osm-roads&mt2=google-hybrid&mt3=esri-satellite&mt4=osm-administrative-boundaries&mt5=mapquest-eu&mt6=bing-hybrid&mt7=mapbox-satellite

[iv] Ayham Dalal, “A Socio-Economic Perspective on the Urbanisation of Zaatari Camp in Jordan,” Migration Letters 12, no. 3 (September 2015), pp. 271.

[v] “Refugee Camps Are the ‘Cities of Tomorrow’, Says Aid Expert,” Dezeen Magazine, November 23, 2015, http://www.dezeen.com/2015/11/23/refugee-camps-cities-of-tomorrow-killian-kleinschmidt-interview-humanitarian-aid-expert/.

[vi] Beehner, “Are Syria’s Do-It-Yourself Refugees Outliers or Examples of a New Norm?”

[vii] In 2014, a second Syrian refugee camp, Azraq, was built in the eastern desert region of Jordan. Learning from the supposed mistakes of Za’atari’s less-than-perfect organization, the UN created Azraq as the newest ‘model’ camp to host as many as 130,000 refugees. Duplicate caravans repeat in monochrome rows, and there is little public space. Only around 30,000 refugees live there as most prefer Za’atari or urban communities to the tin-roofed oasis. Some aid workers described it to me as an “open-air prison.” See more here: http://www.unhcr.org/news/latest/2014/4/5360b21b6/jordan-opens-new-desert-camp-syrian-refugees-azraq.html.

[viii] Michel Agier, “Between War and City: Towards an Urban Anthropology of Refugee Camps,” trans. Richard Nice and Loïc Wacquant, Ethnography 3, no. 3 (September 2002), pp. 322.

[ix] In conversation with the author, February 2016.

[x] Agier, “Between War and City: Towards an Urban Anthropology of Refugee Camps.” pp. 337.

[xi] As quoted in Elizabeth Dunn, “The Failure of Refugee Camps,” Boston Review, September 28, 2015, https://bostonreview.net/editors-picks-world/elizabeth-dunn-failure-refugee-camps.

[xii] David Remnick, “City of the Lost,” The New Yorker, August 26, 2013, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/08/26/city-of-the-lost.

[xiii] All names have been changed to protect the individual.

[xiv] Claudia Martinez Mansell, “How to Navigate a Refugee Settlement,” Places Journal, April 2016, https://placesjournal.org/article/camp-code/.

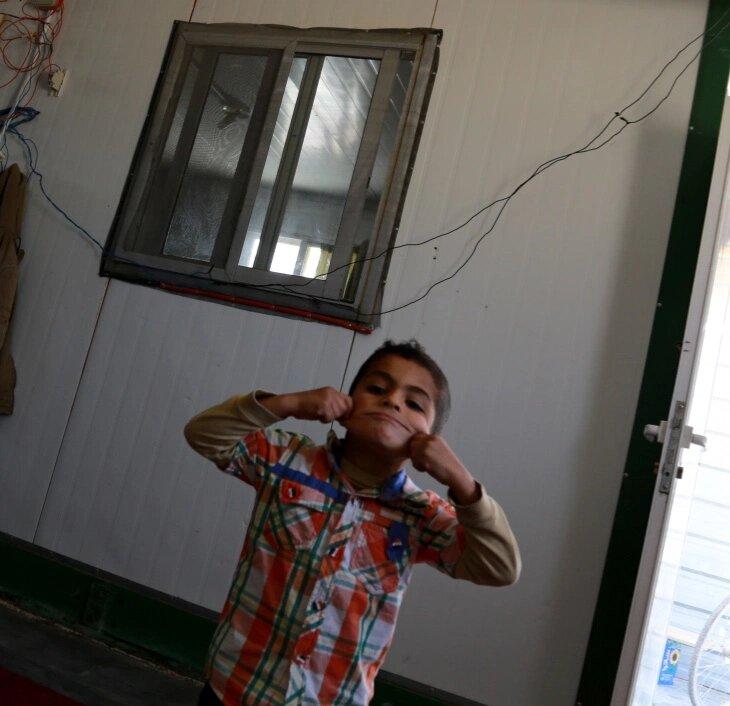

Cover image: Five-year-old Ayman makes silly faces in his caravan in Za’atari. He moved to the camp from Dar’a with his parents and three brothers two and a half years ago. Photo by the author.